On Ash Wednesday our lives round the bend on the road to Jerusalem only to find the hordes of Babylon blocking our way. We are marked with the cross and there can be no avoidance of the fight. This is the imagery used by the nineteenth century Anglican, Father Congreve, SSJE to describe the “advance of Lent.” I can hardly think of anything more appropriate for our meditation:

Lent awakens spiritual hope in us, just as the sight of the enemy awakes the spirit of an army. They were lagging just now, tired with the march, dispirited; but a sudden signal, one turn in the road, shows them the enemy’s lines stretching right across their way. How the men’s hearts leap up: who is [wearied] now? So Lent awakes the energy of hope by showing us our enemy, the reality of the battle of life, of our conflict with evil. We all know that our fifty or seventy years in this world were given to us for a great achievement–to conquer the world, the flesh, and the devil, to win holiness for eternity; but we easily forget this, and slip out of range. But Lent rallies us, reminds us of the seriousness of our moral life, of the reality of sin, of bad tendencies of our childhood not conquered yet, of the strength of sins of the flesh, of pride and temper, of love of the world, of cowardice in confessing Christ, of sloth and depression, of neglect of prayer and the sacraments.

The Two Standards

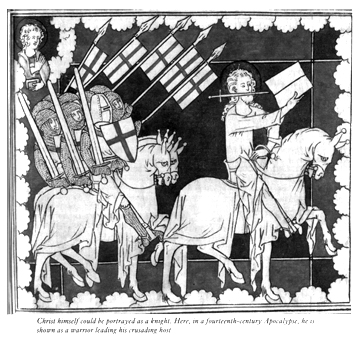

Though Congreve was not Catholic, his imagery reflects one of the most important metaphors used by St. Ignatius in The Spiritual Exercises, namely, the two standards. Christ and Satan are captains of two immense armies that rally around them in the respective regions of Jerusalem and Babylon. For St. Ignatius, this a fundamental image of the spiritual life: mortal strife, that can have only one of two outcomes, heaven or hell.

The strategy of Satan is as simple as it is deadly. St. Ignatius tells us that the demons are sent forth by the Prince of Darkness to tempt us with love for the world: a “longing for riches,” “vain honor” and “vast pride.” He says that it is this love for the world by which he opens the door to every other vice.

But the assets laid to bear against Satan by the Lord are more powerful: “highest poverty,”contumely and contempt, and “humility.” As with the “beatitudes.” This is an inversion of values, the paradox of the gospel: life through death, going up by being brought down.

The Hardest Road

How is a man to in the word but not of the world? How is a man to be a soldier, a knight, and a courageous man without the arrogance and pride that are the tools of Satan? How are we to fight Satan without capitulating to his manipulative and dishonorable methods? In a word, how are we to be wise as serpent and simple as doves? (cf. Mt 10:16).

The first step consists in recognizing that the road that Our Lord took is the hardest road. He remained in the fight to the end and at the same time never sought His own glory and good, but glory of His Father and our salvation. This is the humility of which St. Ignatius speaks. Here is Father Hardon’s commentary on the two standards in which he recommends humility, calmness of spirit and the discernment of spirits as the particular means by which we fight under the standard of Christ and overcome the devil.

Our battle is first of all one that must take place within, but for it to be brought to a victory for Christ, it must be extended to the ends of the earth. It is a fight that we must never concede.

The Abomination of Desolation

Anthony Esolen has written an excellent article, entitled, Where the Battle Was Not Fought, in which he chronicles the woes of the Church in Canada. (Not to pick on Canada, we have our own similar problems in the U.S.) Esolen notes that there is really no place for men, because no one wants to fight, and because virtually no effort has been made to attract men to the faith, let alone to the priesthood.

The spiritual apathy of men, and by which men no longer have a place in the Church—a fight conceded or never fought—leaves us in a desperate situation. For far two long our leaders have largely derelict of their duty, and we are left with the extremes of effeminacy and bravado.

Battle Scars

The solution consists in the rigors of an examined life that is bold enough to make mistakes and get hurt, and humble enough to reassess and revise in order to get it right. This has to happen both spiritually and externally.

Recently, Dawn Eden and William Doino wrote a piece for Busted Halo, in which they called into question the adaptation of Saul Alinsky’s radicalized activist philosophy by conservatives being used against the expert liberal practitioners of that philosophy. In particular, the writers criticized activist James E. O’Keefe for his syncretistic melding of the ideas of Alinsky and that of G.K. Chesterton, and for his practical application of that thinking which included the questionable participation of a young woman who posed as a prostitute in his ACORN exposé videos. Eden and Doino, underscored the utilitarian ethics at the heart of O’Keefe’s methods, taken right out of Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals: “in war the end justifies almost any means.” In a subsequent interview Dawn Eden did not fail to mention that the work of Lila Rose, with whom O’Keefe has also collaborated, and who has been given favorable treatment on AirMaria, is not above critical review.

In response, Christian Hartsock, has penned, or should I say, slashed a rather purple piece of vitriol worthy of Keith Olbermann, in which he ostensibly adopts another rule from Alinsky’s playbook: “ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.” A comparison between the Eden/Doino essay and that of Hartsock, is the difference between a consideration of principles in view of success and a disregard of them justified by success. We can leave everyone free to consider the question, but that the question ought to be considered, seems a difficult thing to reject. That certainty may be something that Alinsky would ridicule, but it is not something that Chesterton would make fun of. On the contrary, for Chesterton such philosophical considerations belonged to the most practical order:

But there are some people, nevertheless—and I am one of them—who think that the most practical and important thing about a man is still his view of the universe. We think that for a landlady considering a lodger, it is important to know his income, but still more important to know his philosophy. We think that for a general about to fight an enemy, it is important to know the enemy’s numbers, but still more important to know the enemy’s philosophy.

The Philosophy of Light

For Chesterton, this consideration of his enemy’s philosophy was not merely a tactical necessity, but a metaphysical and moral requirement, as he infers when he considers the philosophy of George Bernard Shaw. He says that while his intellectual enemy was genuinely “brilliant” and “honest,” his philosophy was “quite solid, quite coherent, and quite wrong.” A man’s philosophy has consequences in the practical order, and so the practical thing to do is

. . . revert to the doctrinal methods of the thirteenth century, inspired by the general hope of getting something done.

Activism, or better, Catholic Action, will ultimately be fruitful only if it is an examined energy, like our own moral lives. It is the hardest road. It is not the merely the rough and tumble road of unchecked prowess, nor is it comfy road of the false courtesy of human respect. It is the hardest road of Christian chivalry. And it is the only way of really “getting something done.”

This is the road we find ourselves on this Ash Wednesday, and the hellish hosts from Babylon will not part and let us pass unmolested. The fight is on, but it begins, continues and ends first within our hearts. Yet, it is always to be fought in the midst of the world that must be conquered for Christ.

Filed under: Catholic Action, Chivalry, Culture, Manliness, Media, News, Politics, Prayers, Pro-Life, Religion, Retreat, Spirituality, Swordplay Tagged: Anthony Esolen, Ash Wednesday, Dawn Eden, G.K. Chesterton, James O’Keefe, Lent, Lila Rose, Saul Alinsky, William Doino

Go to Source