Ave Maria Meditations

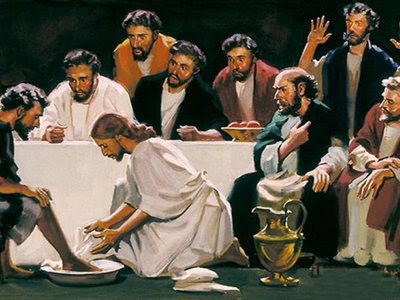

We see then in the scene of the washing of the feet that the Evangelist interprets here not only Christology but also Christian anthropology. I should like to discuss three points illustrating this statement:

- First, seen in this way, not only do the life and death Jesus cohere but also the sacraments of baptism and penance which emerge from the font which is the love of Jesus. The life and death of Jesus, and baptism and penance are together the divine font opening the way to freedom and giving access to the table of life.

- Second, this scene likewise interprets the spiritual content of baptism: the permanent “yes” to love, with faith as the central act of the spiritual life.

- Third, starting from these two points, an ecclesiology and a Christian ethic develop. To accept the washing of feet means entering into the Lord’s action, sharing in it ourselves, letting ourselves be identified with that action. To receive this washing means to continue with Christ to wash the soiled feet of the world. Jesus says, “If I, then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet” (13:14).

These words are not a moral gloss on a dogmatic fact, but rather belong to the very center of Christology. Love is received only by loving. Fraternal love is, in John, inserted into the Trinitarian love. This is the “new commandment,” not in the sense of an external command but as the inner structure of the essence of Christianity.

In this connection it can be interesting to point out how St. John never speaks of a love for all people in general, but only of love within the fraternal community, that is, the baptized. Modern theologians criticize St. John for this fact and speak of an unacceptable restriction of Christianity, of a loss of universality. Certainly, there is a danger here, and complementary texts, like the parable of the good Samaritan and that of the last judgment, are indispensable. But taken in the context of the unity and indivisibility of the New Testament as a whole, John expresses a very important truth: love in the abstract will never have any force in the world if it does not sink its roots in the actual community built on fraternal love. Love’s polity is constructed only by starting out from a small fraternal community. It has to begin from the particular to arrive at the universal. To make openings for fraternity is today no less important than in the time of St. John, or of St. Benedict, who with the fraternity of monks was the true architect of Christian Europe, building models of the new city in a fraternity of faith.

And now, returning to the Gospel, we can say that the account of the washing of the feet has a very literal content. The sacramental structure involves an ecclesial structure, a fraternal structure. This structure implies that Christians have to be ready to offer one another the service of slaves, and that only thus can they bring about the Christian revolution, and construct the New City.

Pope Benedict XVI (Journey to Easter)